| NARMAR / NARAM-SIN / VISHVA

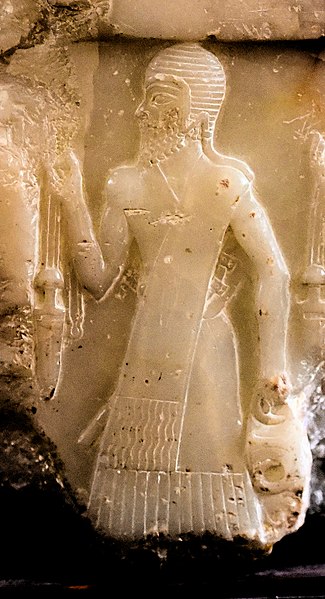

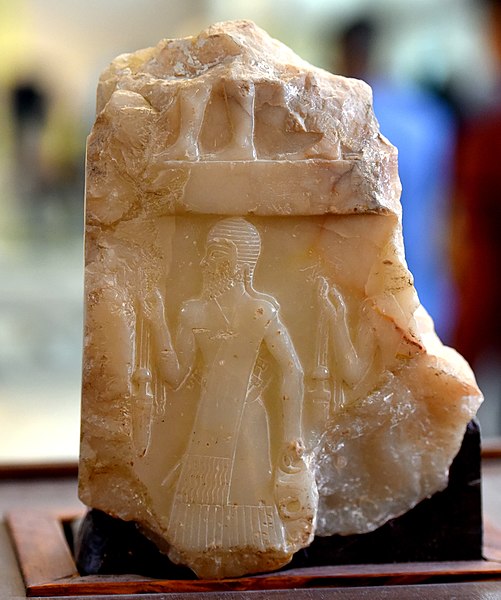

Portrait of Naram-Sin

Narmar / Vishva / Naram-Sin also transcribed Naram-Sîn or Naram-Suen (Akkadian: Na-ra-am Sîn, meaning "Beloved of the Moon God Sîn", the being a silent honorific for "Divine"), was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254 - 2218 BC, and was the third successor and grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin the empire reached its maximum strength. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title "God of Akkad", and the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters, King of the Universe".

Biography

:

Reign :

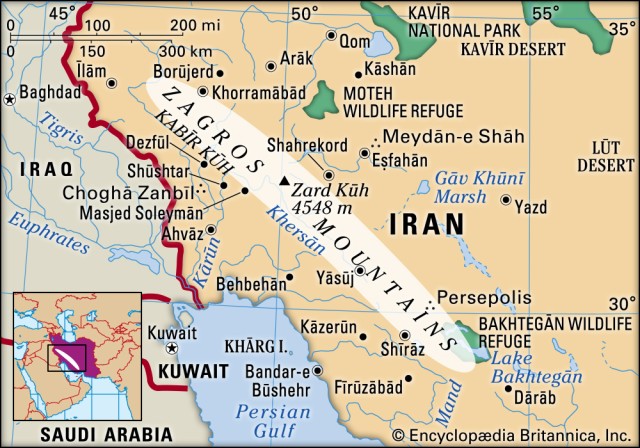

Possible relief of Naram-Sin at Darband-i-Gawr, celebrating his victory over Lullubi king Satuni. Qaradagh Mountain, Sulaymaniyah, Iraqi Kurdistan Naram-Sin defeated Manium of Magan, and various northern hill tribes in the Zagros, Taurus, and Amanus Mountains, expanding his empire up to the Mediterranean Sea and Armenia. His "Victory Stele" depicts his triumph over Satuni, chief of Lullubi in the Zagros Mountains. The king list gives the length of his reign as 56 years, and at least 20 of his year-names are known, referring to military actions against various places such as Uruk and Subartu. One unknown year was recorded as "the Year when Naram-Sin was victorious against Simurrum in Kirasheniwe and took prisoner Baba the governor of Simurrum, and Dubul the ensi of Arame". Other year names refer to his construction work on temples in Akkad, Nippur, and Zabala. He also built administrative centers at Nagar and Nineveh. At one point in his reign much of the empire, led by Iphur-Kis from the city of Kish rose in rebellion and was put down strongly.

Taurus Mountains

Zagros Mountains

Zagros Mountains Submission

of Sumerian kings :

“Naram-Sin, the mighty God of Agade, king of the four corners of the world, Lugalushumgal, the scribe, ensi of Lagash, is thy servant.”

-

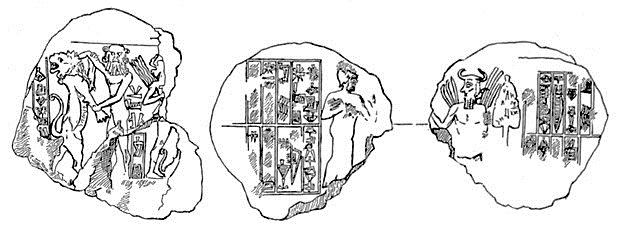

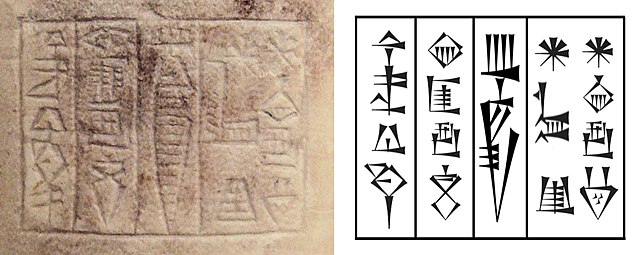

Seal of Lugal-ushumgal as vassal of Naram-sin.

Control of Elam :

Naram-Sin campaigned from Elam in the east, to Ebla and Armanum in the west Elam had been under the domination of Akkad, at least temporarily, since the time of Sargon. The Elamite king Khita is probably recorded as having signed a peace treaty with Naram-Sin, stating: "The enemy of Naram-Sin is my enemy, the friend of Naram-Sin is my friend". It has been suggested that the formal treaty allowed Naram-Sin to have peace on his eastern borders, so that he could deal more effectively with the threat from Gutium. Further study of the treaty suggests that Khita provided Elamite troops to Naram-Sin, that he married his daughter to the Akkadian king, and that he agreed to set up statues of Naram-Sin in the sanctuaries of Susa. As a matter of fact, it is well known that Naram-Sin had extreme influence over Susa during his reign, building temples and establishing inscriptions in his name, and having the Akkadian language replace Elamite in official documents.

During the rule of Naram-Sin, "military governors of the country of Elam" (shakkanakkus) with typically Akkadian names are known, such as Ili-ishmani or Epirmupi. This suggests that these governors of Elam were officials of the Akkadian Empire.

Conquest of Armanum and Ebla :

Akkadian soldier of Naram-Sin, with helmet and long sword, on the Nasiriyah stele. He carries a metal vessel of Anatolian type The conquest of Armanum and Ebla on the Mediterranean coast by Naram-Sin is mentioned in several of his inscriptions:

"Whereas, for all time since the creation of mankind, no king whosoever had destroyed Armanum and Ebla, the god Nergal, by means of (his) weapons opened the way for Naram-Sin, the mighty, and gave him Armanum and Ebla. Further, he gave to him the Amanus, the Cedar Mountain, and the Upper Sea. By means of the weapons of the god Dagan, who magnifies his kingship, Naram-Sin, the mighty, conquered Armanum and Ebla."

-

Inscription of Naram-Sin. E 2.1.4.26

It is thought that the stele represents the result of the campaigns of Naram-Sin to Cilicia or Anatolia. This is suggested by the characteristics of the booty carried by the soldiers in the stele, especially the metal vessel carried by the main soldier, the design of which is unknown in Mesopotamia, but on the contrary well known in contemporary Anatolia.

Soldier with sword, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin

Naked captives, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin The Curse of Akkad :

Victory

Stele of Naram-Sin, c. 2230 BC. It shows him defeating the Lullibi,

a tribe in the Zagros Mountains, and their king Satuni, trampling

them and spearing them. Satuni, standing right, is imploring Naram-Sin

to save him. Naram-Sin is also twice the size of his soldiers. In

the 12th century BC it was taken to Susa, where it was found in

1898.

Video Icon Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Smarthistory

One Mesopotamian myth, a historiographic poem entitled "The curse of Akkad: the Ekur avenged", explains how the empire created by Sargon of Akkad fell and the city of Akkad was destroyed. The myth was written hundreds of years after Naram-Sin's life and is the poet's attempt to explain how the Gutians succeeded in conquering Sumer. After an opening passage describing the glory of Akkad before its destruction, the poem tells of how Naram-Sin angered the chief god Enlil by plundering the Ekur (Enlil's temple in Nippur.) In his rage, Enlil summoned the Gutians down from the hills east of the Tigris, bringing plague, famine and death throughout Mesopotamia. Food prices became vastly inflated, with the poem stating that 1 lamb would buy only half a sila (about 425 ml) of grain, half a sila of oil, or half a mina (about 250g) of wool. To prevent this destruction, eight of the gods (namely Inanna, Enki, Sin, Ninurta, Utu, Ishkur, Nusku, and Nidaba) decreed that the city of Akkad should be destroyed in order to spare the rest of Sumer and cursed it. This is exactly what happens, and the story ends with the poet writing of Akkad's fate, mirroring the words of the gods' curse earlier on :

Its

chariot roads grew nothing but the 'wailing plant,'

Gutian

Incursions :

Victory stele :

Naram-Sin's Victory Stele depicts him as a god-king (symbolized by his horned helmet) climbing a mountain above his soldiers, and his enemies, the defeated Lullubi led by their king Satuni. Although the stele was broken off at the top when it was stolen and carried off by the Elamite forces of Shutruk-Nakhunte in the 12th century BCE, it still strikingly reveals the pride, glory, and divinity of Naram-Sin. The stele seems to break from tradition by using successive diagonal tiers to communicate the story to viewers, however the more traditional horizontal frames are visible on smaller broken pieces. It is six feet and seven inches tall, and made from pink limestone. The stele was found at Susa, and is now in the Louvre Museum. A similar bas-relief depicting Naram-Sin was found a few miles north-east of Diarbekr, at Pir Hüseyin.

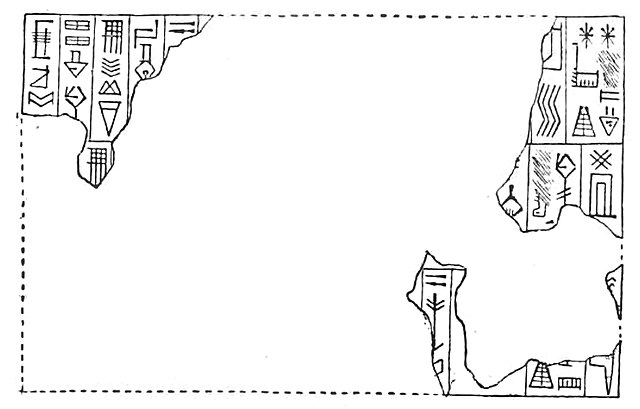

The inscription over the head of the king is in Akkadian and fragmentary, but reads :

"Naram-Sin the powerful . . . . Sidur and Sutuni, princes of the Lulubi, gathered together and they made war against me."

-

Akkadian inscription of Naram-Sin.

Children

:

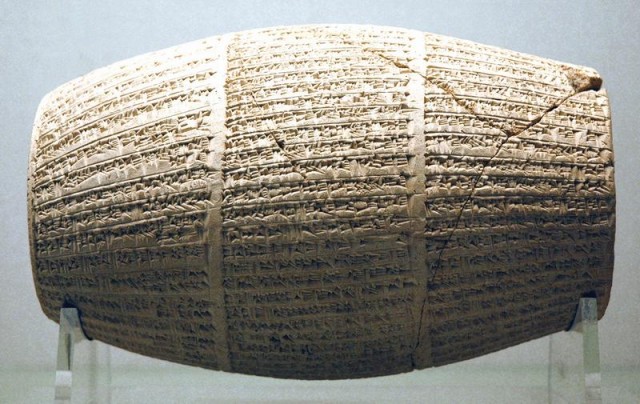

Excavations by Nabonidus circa 550 BCE :

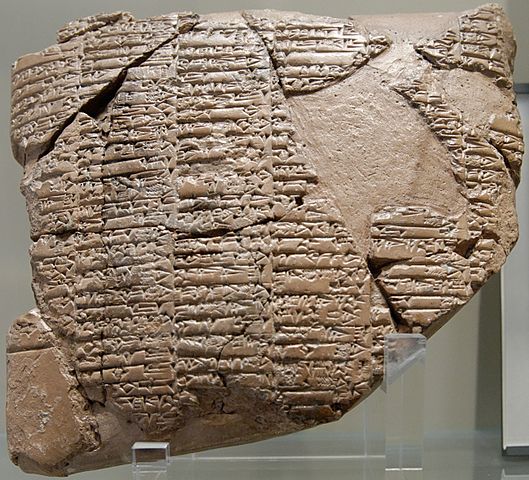

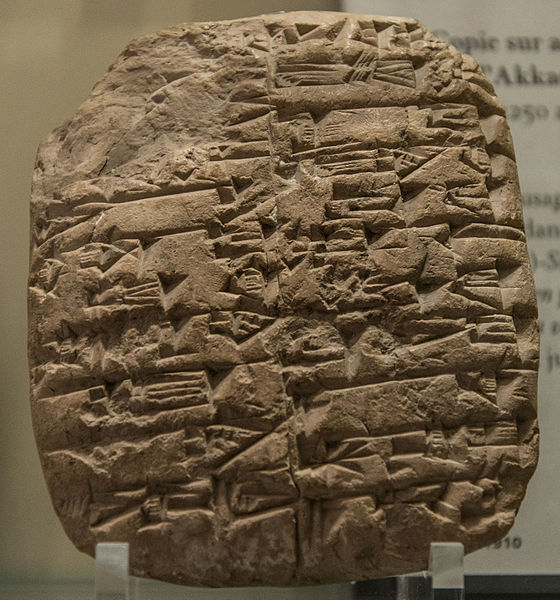

Extract describing the excavation Cuneiform account of the excavation of a foundation deposit belonging to Naram-Sin (ruled c. 2200 BCE), by king Nabonidus (ruled c. 550 BCE) A foundation deposit of Naram-Sin was discovered and analysed by king Nabonidus, circa 550 BCE, who is thus known as the first archaeologist. Not only did he lead the first excavations which were to find the foundation deposits of the temples of Šamaš the sun god, the warrior goddess Anunitu (both located in Sippar), and the sanctuary that Naram-Sin built to the moon god, located in Harran, but he also had them restored to their former glory. He was also the first to date an archaeological artifact in his attempt to date Naram-Sin's temple during his search for it. Even though his estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years, it was still a very good one considering the lack of accurate dating technology at the time.

Inscriptions :

Seals in the name of Naram-Sin

Treaty of alliance between Naram-Sin and Khita of Susa, king of Awan, c. 2250, Susa, Louvre Museum

Stele of the Akkadian king Naram-Sin. The "-ra-am" and "-sin" parts of the name "Naram-Sin" appear in the broken top right corner of the inscription, traditionally reserved for the name of the ruler. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Portrait of Naram-Sin (detail)

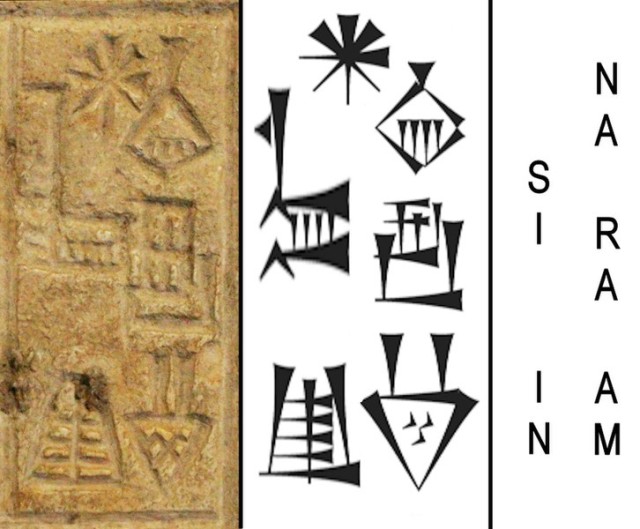

The name "Naram-Sin" in cuneiform on an inscription. The star symbol is a silent honorific for "Divine", Sîn (Moon God) is specially written with the characters "EN-ZU"

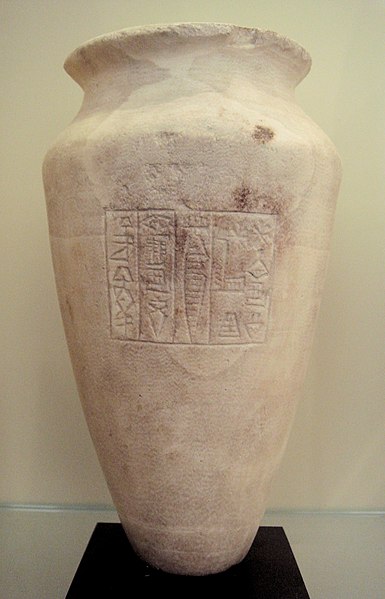

Alabaster vase in the name of "Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(Na-ra-am Sîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, circa 2250 BCE. Louvre Museum AO 74

"Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(Na-ra-am Sîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, circa 2250 BCE. Louvre Museum AO 74

This bronze head traditionally attributed to Sargon is now thought to actually belong to his grandson Naram-Sin

Fragment of a stone bowl with an inscription of Naram-Sin, and a second inscription by Shulgi (upside down). Ur, Iraq. British Museum

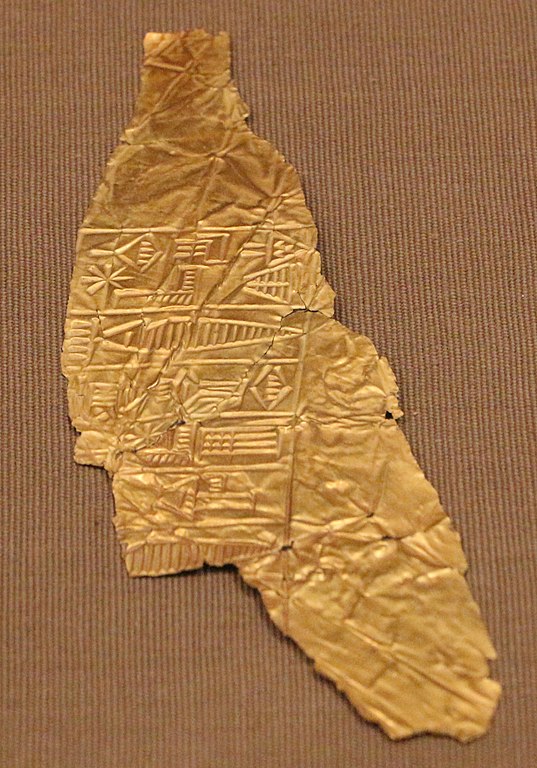

Gold foil in the name of Naram-Sin

Copy of an inscription of Naram-Sin. Louvre Museum AO 5475

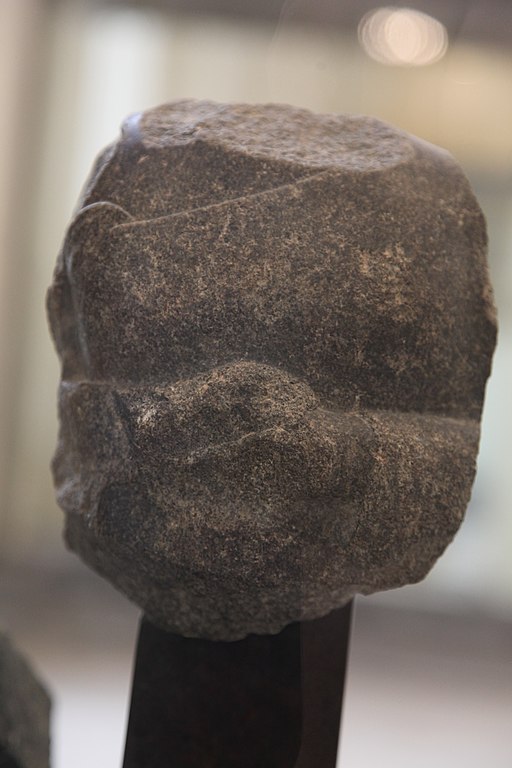

Diorite base of statue of Naram-sin

Fragment of a statue in the name of Naram-Sin, Louvre Museum Sb 53 Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)