| KHAMMURABI / HAMMURABI / PUNDRIK

Hammurabi (standing), depicted as receiving his royal insignia from Shamash (or possibly Marduk). Hammurabi holds his hands over his mouth as a sign of prayer (relief on the upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws).

Pundrik / Khammurabi / Hammurabi (c. 1810 – c. 1750 BC) was the sixth king of the First Babylonian dynasty of the Amorite tribe, reigning from c. 1792 BC to c. 1750 BC (according to the Middle Chronology). He was preceded by his father, Nabhas / Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states of Larsa, Eshnunna, and Mari. He ousted Ishme-Dagan I, the king of Assyria, and forced his son Mut-Ashkur to pay tribute, bringing almost all of Mesopotamia under Babylonian rule.

Pundrika / Khammurabi / Hammurabi is best known for having issued the Code of Hammurabi, which he claimed to have received from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice. Unlike earlier Sumerian law codes, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, which had focused on compensating the victim of the crime, the Law of Hammurabi was one of the first law codes to place greater emphasis on the physical punishment of the perpetrator. It prescribed specific penalties for each crime and is among the first codes to establish the presumption of innocence. Although its penalties are extremely harsh by modern standards, they were intended to limit what a wronged person was permitted to do in retribution. The Code of Hammurabi and the Law of Moses in the Torah contain numerous similarities.

Pundrika / Khammurabi / Hammurabi was seen by many as a god within his own lifetime. After his death, Hammurabi was revered as a great conqueror who spread civilization and forced all peoples to pay obeisance to Marduk, the national god of the Babylonians. Later, his military accomplishments became de-emphasized and his role as the ideal lawgiver became the primary aspect of his legacy. For later Mesopotamians, Hammurabi's reign became the frame of reference for all events occurring in the distant past. Even after the empire he built collapsed, he was still revered as a model ruler, and many kings across the Near East claimed him as an ancestor. Hammurabi was rediscovered by archaeologists in the late nineteenth century and has since been seen as an important figure in the history of law.

Reign and conquests :

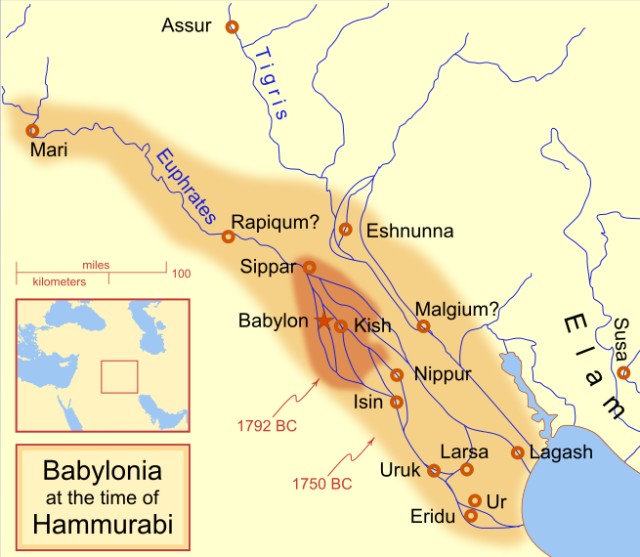

Map showing the Babylonian territory upon Hammurabi's ascension in c. 1792 BC and upon his death in c. 1750 BC Hammurabi was an Amorite First Dynasty king of the city-state of Babylon, and inherited the power from his father, Sin-Muballit, in c. 1792 BC. Babylon was one of the many largely Amorite ruled city-states that dotted the central and southern Mesopotamian plains and waged war on each other for control of fertile agricultural land. Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian culture gained a degree of prominence among the literate classes throughout the Middle East under Hammurabi. The kings who came before Hammurabi had founded a relatively minor City State in 1894 BC, which controlled little territory outside of the city itself. Babylon was overshadowed by older, larger, and more powerful kingdoms such as Elam, Assyria, Isin, Eshnunna, and Larsa for a century or so after its founding. However, his father Sin-Muballit had begun to consolidate rule of a small area of south central Mesopotamia under Babylonian hegemony and, by the time of his reign, had conquered the minor city-states of Borsippa, Kish, and Sippar.

Thus Hammurabi ascended to the throne as the king of a minor kingdom in the midst of a complex geopolitical situation. The powerful kingdom of Eshnunna controlled the upper Tigris River while Larsa controlled the river delta. To the east of Mesopotamia lay the powerful kingdom of Elam, which regularly invaded and forced tribute upon the small states of southern Mesopotamia. In northern Mesopotamia, the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad I, who had already inherited centuries old Assyrian colonies in Asia Minor, had expanded his territory into the Levant and central Mesopotamia, although his untimely death would somewhat fragment his empire.

The first few years of Hammurabi's reign were quite peaceful. Hammurabi used his power to undertake a series of public works, including heightening the city walls for defensive purposes, and expanding the temples. In c.1801 BC, the powerful kingdom of Elam, which straddled important trade routes across the Zagros Mountains, invaded the Mesopotamian plain. With allies among the plain states, Elam attacked and destroyed the kingdom of Eshnunna, destroying a number of cities and imposing its rule on portions of the plain for the first time.

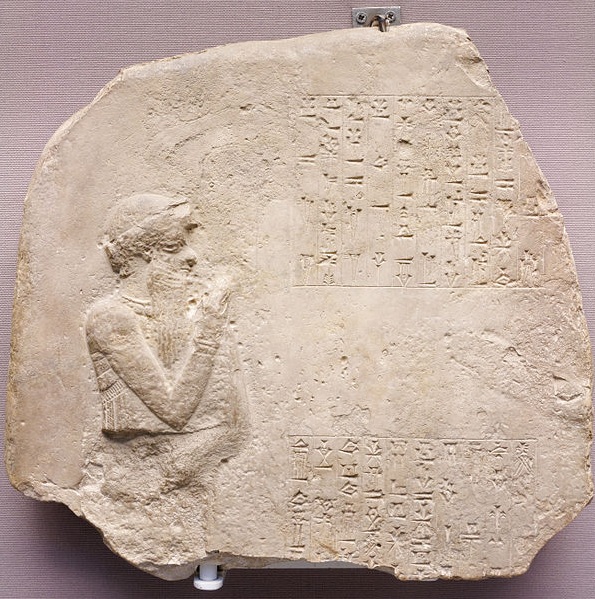

A limestone votive monument from Sippar, Iraq, dating to c. 1792 – c. 1750 BC showing King Hammurabi raising his right arm in worship, now held in the British Museum

This bust, known as the "Head of Hammurabi", is now thought to predate Hammurabi by a few hundred years (Louvre) In order to consolidate its position, Elam tried to start a war between Hammurabi's Babylonian kingdom and the kingdom of Larsa. Hammurabi and the king of Larsa made an alliance when they discovered this duplicity and were able to crush the Elamites, although Larsa did not contribute greatly to the military effort. Angered by Larsa's failure to come to his aid, Hammurabi turned on that southern power, thus gaining control of the entirety of the lower Mesopotamian plain by c. 1763 BC.

As Hammurabi was assisted during the war in the south by his allies from the north such as Yamhad and Mari, the absence of soldiers in the north led to unrest. Continuing his expansion, Hammurabi turned his attention northward, quelling the unrest and soon after crushing Eshnunna. Next the Babylonian armies conquered the remaining northern states, including Babylon's former ally Mari, although it is possible that the conquest of Mari was a surrender without any actual conflict.

Hammurabi entered into a protracted war with Ishme-Dagan I of Assyria for control of Mesopotamia, with both kings making alliances with minor states in order to gain the upper hand. Eventually Hammurabi prevailed, ousting Ishme-Dagan I just before his own death. Mut-Ashkur, the new king of Assyria, was forced to pay tribute to Hammurabi.

In just a few years, Hammurabi succeeded in uniting all of Mesopotamia under his rule. The Assyrian kingdom survived but was forced to pay tribute during his reign, and of the major city-states in the region, only Aleppo and Qatna to the west in the Levant maintained their independence. However, one stele of Hammurabi has been found as far north as Diyarbekir, where he claims the title "King of the Amorites".

Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, have been discovered, as well as 55 of his own letters. These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking care of Babylon's massive herds of livestock. Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son Samsu-iluna in c. 1750 BC, under whose rule the Babylonian empire quickly began to unravel.

Code of laws :

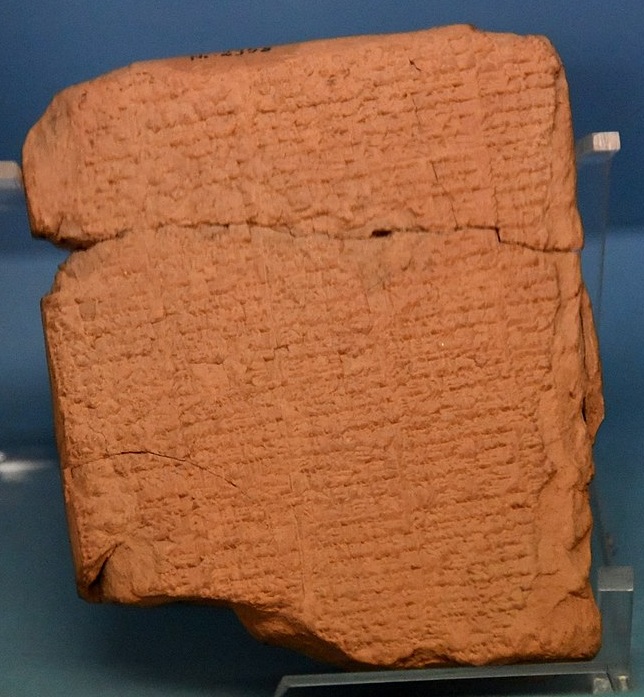

Law code of Hammurabi, a smaller version of the original law code stele. Terracotta tablet, from Nippur, Iraq, c. 1790 BC. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul The Code of Hammurabi is not the earliest surviving law code; it is predated by the Code of Ur-Nammu, the Laws of Eshnunna, and the Code of Lipit-Ishtar. Nonetheless, the Code of Hammurabi shows marked differences from these earlier law codes and ultimately proved more influential.

The Code of Hammurabi was inscribed on a stele and placed in a public place so that all could see it, although it is thought that few were literate. The stele was later plundered by the Elamites and removed to their capital, Susa; it was rediscovered there in 1901 in Iran and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The code of Hammurabi contains 282 laws, written by scribes on 12 tablets. Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore be read by any literate person in the city. Earlier Sumerian law codes had focused on compensating the victim of the crime, but the Code of Hammurabi instead focused on physically punishing the perpetrator. The Code of Hammurabi was one of the first law code to place restrictions on what a wronged person was allowed to do in retribution.

The structure of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified punishment. The punishments tended to be very harsh by modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the use of the "Eye for eye, tooth for tooth" (Lex Talionis "Law of Retaliation") philosophy. The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence. However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment.

A carving at the top of the stele portrays Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice, and the preface states that Hammurabi was chosen by Shamash to bring the laws to the people.Parallels between this narrative and the giving of the Covenant Code to Moses by Yahweh atop Mount Sinai in the Biblical Book of Exodus and similarities between the two legal codes suggest a common ancestor in the Semitic background of the two. Nonetheless, fragments of previous law codes have been found and it is unlikely that the Mosaic laws were directly inspired by the Code of Hammurabi. Some scholars have disputed this; David P. Wright argues that the Jewish Covenant Code is "directly, primarily, and throughout" based upon the Laws of Hammurabi. In 2010, a team of archaeologists from Hebrew University discovered a cuneiform tablet dating to the eighteenth or seventeenth century BC at Hazor in Israel containing laws clearly derived from the Code of Hammurabi.

Legacy

:

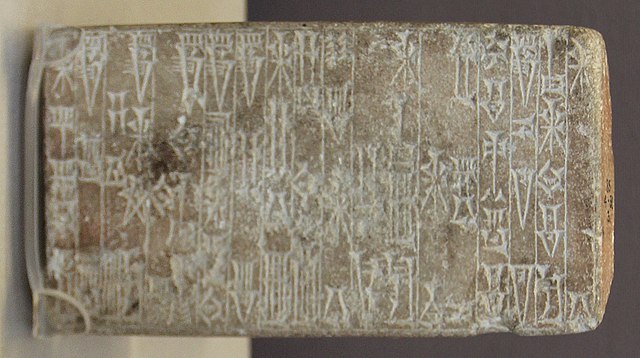

Tablet of Hammurabi (4th column from the right), King of Babylon. British Museum I am the king, the brace that grasps wrongdoers, that makes people of one mind,

After extolling Hammurabi's military accomplishments, the hymn finally declares: "I am Hammurabi, the king of justice." In later commemorations, Hammurabi's role as a great lawgiver came to be emphasized above all his other accomplishments and his military achievements became de-emphasized. Hammurabi's reign became the point of reference for all events in the distant past. A hymn to the goddess Ishtar, whose language suggests it was written during the reign of Ammisaduqa, Hammurabi's fourth successor, declares: "The king who first heard this song as a song of your heroism is Hammurabi. This song for you was composed in his reign. May he be given life forever!" For centuries after his death, Hammurabi's laws continued to be copied by scribes as part of their writing exercises and they were even partially translated into Sumerian.

Political legacy :

Copy of Hammurabi's stele usurped by Shutruk-Nahhunte I. The stele was only partially erased and was never re-inscribed During the reign of Hammurabi, Babylon usurped the position of "most holy city" in southern Mesopotamia from its predecessor, Nippur. Under the rule of Hammurabi's successor Samsu-iluna, the short-lived Babylonian Empire began to collapse. In northern Mesopotamia, both the Amorites and Babylonians were driven from Assyria by Puzur-Sin a native Akkadian-speaking ruler, c. 1740 BC. Around the same time, native Akkadian speakers threw off Amorite Babylonian rule in the far south of Mesopotamia, creating the Sealand Dynasty, in more or less the region of ancient Sumer. Hammurabi's ineffectual successors met with further defeats and loss of territory at the hands of Assyrian kings such as Adasi and Bel-ibni, as well as to the Sealand Dynasty to the south, Elam to the east, and to the Kassites from the northeast. Thus was Babylon quickly reduced to the small and minor state it had once been upon its founding.

The coup de grace for the Hammurabi's Amorite Dynasty occurred in 1595 BC, when Babylon was sacked and conquered by the powerful Hittite Empire, thereby ending all Amorite political presence in Mesopotamia.However, the Indo-European-speaking Hittites did not remain, turning over Babylon to their Kassite allies, a people speaking a language isolate, from the Zagros mountains region. This Kassite Dynasty ruled Babylon for over 400 years and adopted many aspects of the Babylonian culture, including Hammurabi's code of laws. Even after the fall of the Amorite Dynasty, however, Hammurabi was still remembered and revered. When the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte I raided Babylon in 1158 BC and carried off many stone monuments, he had most of the inscriptions on these monuments erased and new inscriptions carved into them. On the stele containing Hammurabi's laws, however, only four or five columns were wiped out and no new inscription was ever added. Over a thousand years after Hammurabi's death, the kings of Suhu, a land along the Euphrates river, just northwest of Babylon, claimed him as their ancestor.

Modern rediscovery :

The bas-relief of Hammurabi at the United States Congress In the late nineteenth century, the Code of Hammurabi became a major center of debate in the heated Babel und Bibel ("Babylon and Bible") controversy in Germany over the relationship between the Bible and ancient Babylonian texts. In January 1902, the German Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch gave a lecture at the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin in front of the Kaiser and his wife, in which he argued that the Mosaic Laws of the Old Testament were directly copied off the Code of Hammurabi. Delitzsch's lecture was so controversial that, by September 1903, he had managed to collect 1,350 short articles from newspapers and journals, over 300 longer ones, and twenty-eight pamphlets, all written in response to this lecture, as well as the preceding one about the Flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh. These articles were overwhelmingly critical of Delitzsch, though a few were sympathetic. The Kaiser distanced himself from Delitzsch and his radical views and, in fall of 1904, Delitzsch was forced to give his third lecture in Cologne and Frankfurt am Main rather than in Berlin. The putative relationship between the Mosaic Law and the Code of Hammurabi later became a major part of Delitzsch's argument in his 1920–21 book Die große Täuschung (The Great Deception) that the Hebrew Bible was irredeemably contaminated by Babylonian influence and that only by eliminating the human Old Testament entirely could Christians finally believe in the true, Aryan message of the New Testament. In the early twentieth century, many scholars believed that Hammurabi was Amraphel, the King of Shinar in the Book of Genesis 14:1. This view has now been largely rejected, and Amraphael's existence is not attested in any writings from outside the Bible.

Because of Hammurabi's reputation as a lawgiver, his depiction can be found in several United States government buildings. Hammurabi is one of the 23 lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol. A frieze by Adolph Weinman depicting the "great lawgivers of history", including Hammurabi, is on the south wall of the U.S. Supreme Court building. At the time of Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi Army's 1st Hammurabi Armoured Division was named after the ancient king as part of an effort to emphasize the connection between modern Iraq and the pre-Arab Mesopotamian cultures.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |